- Home

- Jo Watson Hackl

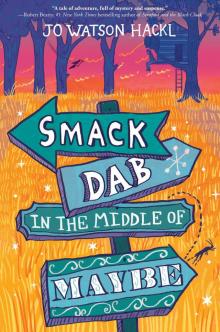

Smack Dab in the Middle of Maybe Page 3

Smack Dab in the Middle of Maybe Read online

Page 3

“Alive?” I thought I’d heard her wrong.

“Yes, baby.” Mama closed her eyes. “There were birds dancing on the walls, moving in the light. A skinny man with paint all over his clothes came out of that room and invited me in. Said his name was Bob.”

Mama snuggled me closer. “That room had every kind of bird you can think of—cardinals, woodpeckers, hummingbirds, doves, even crows. But the one I liked best was a watermelon-red bird with black wings. It fluttered its wings at me.”

“What kind of bird was it?” I asked.

“Bob said it was a boy scarlet tanager and you have to be lucky to see one, even once. It mostly stays high in the treetops and flies through Mississippi only certain times of year, on its way to and from flying over a thousand miles to spend the winter in South America. In the fall, its red feathers start to turn green.

“Just imagine.” She turned to look me straight in the eyes. “A bird that could change itself to fly someplace new.”

Mama’s eyes went to the tree line. “I knew it the instant I saw that bird—the world didn’t have to be plain and boring. It could be bright and bold and exciting. I didn’t have to settle for ordinary.” Mama flicked a speck of dirt out from under her fingernail. “I wanted to be like that bird.”

I grabbed her hand and held it tight. I wanted my mama to stay my mama. But for her, I tried to picture that bird changing colors and looking at the world from up high. “What else was in that room?”

Mama looked back at me. I could tell her mind was still in that room. “Everything. Flowers and trees and vines and squirrels and birds and fish. I told Bob it was my birthday and seeing that room was the best birthday present I ever got. That made him smile. He said I’d shown up at exactly the right time, and he made me promise to come back and see the room when he was done. He asked me if I liked puzzles, and I said yes. He told me that since it was my birthday, he was going to give me a present—he’d tell me a secret he hadn’t shared with a single soul. He lowered his voice and said that after he finished the room, he was going to leave a clue trail. If I solved it, I’d find a buried surprise. Then he handed me this.”

Mama pulled something out of her pocket and pressed it in my hand. “He said it was the first clue.”

Mama had handed me a tiny, round painting, colored on both sides. It was just big enough to fit between the circle of my thumb and first finger. “Thanks, Mama.” It felt cold in my hand and heavy for its size and was covered in green, black, and red paint, the colors blending into one another.

At first, it just looked blurry. But when I squinted at it, the faintest outline of a red bird with black wings appeared. It looked ready to fly off.

“A tanager,” I said. “One of your dancing birds.”

Mama grinned. “I knew you’d see it, baby.”

“So, did you go back to visit the room? Did you solve the clue trail?”

Mama took my hand again, her grip tight. “No. When I told Mama and Daddy about it, they didn’t believe me. You know how Grandma is—always telling me to get my head out of the clouds, to be more practical. She and Daddy said paintings don’t come to life. Instead of a painting, all they saw was one big blur. They said it was just junk. Mama and Daddy started saying I was getting too excited over nothing. Later, they tried to put me on medicine for it. But my Bird Room is real, Cricket. It was alive. And one day I’ll prove it. I won’t stop looking till I find it.”

Mama stroked her thumb across my first finger like she wanted to make sure I was still there. “But for now, this is a little piece of magic—just like you. I want you to have it. I’ve been waiting seven years to give it to you. You have the eye, baby. You can see it.”

Every night since then, I slept with that painted tanager under my pillow. Even after I had to go live with Aunt Belinda.

Which was a mistake.

My very first Saturday there, I woke up to the sound of a firecracker exploding and all three cousins laughing their heads off and running. What was left of my painting was in the middle of my bedroom floor with blown-off paint chips all around it.

But maybe my cousins did me a favor.

Because when I went to pick it up, I saw what was under all those layers of paint—a metal coin. I flaked off the rest of the paint. The coin was shiny as a nickel, but like nothing I’d ever seen before. One side was almost all taken up with an outline of a lightbulb with little rays coming out from it, all in raised-up metal. Below the lightbulb, Good for $1.00 in merchandise. The other side read, Not transferable. Electric Lumber Company, Electric City, Mississippi.

I was holding a doogaloo, the coin they’d taught us about in school.

Those coins came from only one place.

Mama was wrong—that Bird Room wasn’t in a house far away.

Something right here in this ghost town was tied to Mama’s Bird Room.

It’s not every day you get to set up a clue-finding base camp and make it any which way you want.

I divided the tree-house ledges into our food shelf, our supply shelf, and our clue shelf. Mama would be here in eleven days to see that headstone. With the food from Thelma’s and just a little bit of living off the land, I’d have enough to keep me going for clue finding.

I propped the doogaloo on my clue shelf. Me and Charlene, we’d fill in more clues later.

“We can do this,” I told Charlene. Daddy always said these woods were his own private museum and general store. Something new to look at every day, and everything he needed. I’d make these woods my museum and store, too.

Okay, so I didn’t exactly know how we were supposed to solve an over thirty-year-old clue trail. But Mama said the doogaloo was the first clue. And we were in the town where it came from. The Bird Room and the rest of the clues had to be close by.

I got busy. The food shelf was easy. The supplies took longer. Daddy’s book was where he always left it, sealed in a plastic bag in the army surplus box in the corner. The book still smelled like Daddy—all Dial soap and sawdust—with a bit of the smoke smell from our hot-dog campfires. The bag his book had come out of could be a supply, so I put that on the shelf. The box held other things I might need—the skillet, pot, plates, silverware, cups, and a little roll of wire. I put them all on my supply shelf next to my matches, clothesline, and hand shovel.

I brought in some dirt and crunched-up leaves from outside and laid them in the box. “Your cozy house.” I slid Charlene in.

We’d need blankets. I sawed off some waist-high pine branches with Daddy’s pocketknife, the way Daddy showed me that time we forgot our sleeping bags. Laying the branches out straight, I ran a row of duct tape across them, turned them over, and did the same thing on the other side.

Using the last of the tape, I made a blanket lid for the top of Charlene’s box.

To keep us extra warm, I hauled in some pine limbs and piled them against the walls. Pine needles should help hold in the heat, right? I added some berry sprigs I found for decoration. That part came from Mama. “Seek the beauty.”

Next was water. Me and Daddy always toted that in with us, but a branch of the creek wasn’t far, and I scooped up a panful of water. I’d need to boil it before I could drink it, so I grabbed the matches.

Beside the tree house, cement steps took me to a walk-in basement missing its house. Daddy’d told me the story about the mill superintendent’s wife. Deathly afraid of tornadoes, she made them build her a full basement, complete with fireplace. The mill couldn’t load up a basement, so they only took the top half of the house, floor and all. We’d added a grate Mama had welded to the fireplace for our campfires, and it still looked sturdy.

The woods gave me branches to break up to build a fire. In a way, it was like being back at Thelma’s, picking things off the shelves. To tell you the truth, it was kind of fun.

Me and Daddy always started our fire

s with candle wax, dryer lint, and sometimes lip balm. “General store,” I said, and scooped up two armfuls of twigs and dead leaves for kindling.

When the match caught, the flame threw off shimmering shadows. I couldn’t believe it—I’d started a fire all by myself. For that one second, it felt like Mama and Daddy were right there next to me, cheering me on. I pushed three rocks into the fire. Daddy used to do that in our old fireplace to make foot warmers whenever we lost power.

The bird squawks had ended. An owl called. It didn’t seem to mind me and Charlene being out here in the woods. A kink unhooked itself from my shoulders.

I’d beaten the dark.

Me and Charlene had a picnic on the tiny tree-house porch, the way me and Daddy used to do. It was cold, but we had us a proper meal, with apple, jerky, and a spoonful of peanut butter for me, and a sliver of apple for Charlene. If I stuck to two pieces of jerky a day, I could make it last till Mama.

For dessert, I savored every last crumb of one of the Little Debbies, no cousins around to take it. I eyed the candy bar, with its peanuts and caramel and chocolate deliciousness. Nope. I’d save that for later.

Squirrels chattered in a nest in the branches above us. So me and Charlene would have friendly neighbors.

“Tomorrow, we’ll find more food,” I told Charlene. “And we’ll start looking for clues.”

I pulled out Daddy’s book to read up on things I could eat. But something else caught my attention—notes in Daddy’s handwriting next to certain sections.

WHEN CRICKET’S 12.

Sure enough, we’d already covered how to build a fire.

WHEN CRICKET’S 10.

Check. The different types of trees. Then I came to the part about living off the land.

WHEN CRICKET’S 13—WOODS TIME TOGETHER.

Those words hit me hard. Woods Time was here whether I was ready for it or not.

Just then, the first star appeared in the sky.

I leaned out to make a wish.

My wish was just one word—Mama.

I closed my eyes to make the wish extra strong. Soon as I did, though, I smelled something—hickory smoke. And it was closer than any fire should have been.

Nobody lived to the east, where the smoke came from. A second-cousin branch of Daddy’s family used to own that part of the woods before they had a falling-out. Years of squabbling made sure that land stayed just as bare as it was the day the lumber company left.

Who is out there?

Campers? Hunters? Me and Daddy had run across hikers and hunters and their campfires out here from time to time. Was it somebody who might see my fire and turn me in for running away?

I climbed down, sprinted to the fireplace, scattered the coals, and ran back to the tree house.

Smoke from my fire squiggled into a question mark and faded.

Which left me and Charlene alone in the dark with the owl and the wind and who knew what else?

I couldn’t see Charlene, but I heard her. She was hunkering down, drawing the dirt and leaves around her, bit by creaky bit.

Lying down on those sweatshirts, I drew the dark around me, too. I tried to think of Mama’s songs, the way she’d sing “Amazing Grace” and sometimes Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire.” I tried to picture every little tug at the corner of her mouth the last time she sang to me, some clue that she was thinking about running off. Things I’d have noticed if I’d been paying attention good.

* * *

Charlene woke me up. Yant, yant, YANT, yant. Yant, yant, YANT, yant.

The sky was thick dark. Coyotes howled far off. From below us came sounds I couldn’t put a name to. Sounds I might not ever want to put a name to. I was hoping it was just deer.

With Charlene next to me, though, I wasn’t as scared as you’d think.

Charlene was missing somebody, too.

Hearing Charlene was like having somebody say, right out loud, something so deep inside me I hadn’t found the words to put to it yet.

A single cricket answered back from deep in the woods, probably protected in an old homeplace. Yant, yant, YANT, yant. Yant, yant, YANT, yant. Charlene kept up her rhythm, but she didn’t try to hop out of her box. Maybe it was enough just to know that somebody else was out there. Yant, yant, YANT, yant. I pretended it was calling for the both of us.

* * *

I heard the morning before I saw the light. Birds singing. Crows cawing to each other. Squirrels scampering on our roof.

The birds weren’t squawking at us anymore. But everything felt off balance. My arm was asleep. My shirt stuck to my skin. My empty stomach churned. Aunt Belinda’s house, even with my cousins and their Cheez Doodle fingers, sounded pretty good to me. If I were back there, Aunt Belinda would be standing at the stove in her electric curlers, frying up a mess of eggs and pouring us both coffee, making mine half cream.

The tiptoe morning light started sifting through the tree limbs.

No sign of smoke.

Charlene chirped, reminding me we needed to get started. But we’d need to be careful.

Ten days to find proof of the room Mama hadn’t been able to find after a whole lifetime of searching.

But Mama hadn’t known about the doogaloo. She’d probably been looking in the wrong places.

Still, how do you find a Bird Room in a town that’s missing its houses? What if the Bird Room house got hauled off?

“We don’t have to find the room,” I told Charlene. “We just need to find something that proves the Bird Room used to be here.”

I ate two pieces of jerky and set out for the sidewalks. Anything could be a clue. At each old homesite, I studied the columns, looking for a sign of…I didn’t know exactly what. But something tied to Mama’s room.

Block by block, I prowled. Nothing unusual. Just tipped-over pillars and overgrown yards.

My eye caught on a porch step. THE JOHNSON FAMILY. Four seashells.

Why hadn’t I noticed that before?

I backtracked and started the search over, this time looking at the columns and steps, checking through the weeds for any more basements.

Lots of names. A few handprints, some pressed leaves, and one dogwood flower were in the chipping concrete steps. Nothing that looked like it might be a clue.

By this time, my stomach was growling something awful.

I trudged back to the tree house and eyed the candy bar. “Just for an emergency,” I told Charlene. I chomped into an apple instead.

I hadn’t found a single clue all morning. If I was going to solve a whole clue trail, I needed to try something else. Then I remembered how Grandma loved to read mysteries. She always solved the clues before the end.

I’d go ask Grandma for help.

All I could think about, as I dodged the cracks in the sidewalks on the way to the cemetery, was when I’d been there with Mama last summer. Mama didn’t keep many regular habits, but visiting Grandma’s grave was one thing she stuck to.

And that July day, Mama took me with her. She told me to wait in the car, but I wanted to be where Mama was. When I snuck out to find her, Mama was swaying over Grandma’s grave. A propped-up plywood board stood where the headstone should have been.

Mama ran her fingers along the plywood. “I promised you. I know I promised you.” Her voice cracked, and she drew back like she’d just touched fire.

I couldn’t watch. I slunk back to the car.

When Mama yanked the car door open, her face was hard. All the way home, she hung her hand out the window and parted the breeze back and forth, back and forth.

I just sat there watching Mama, hoping she wouldn’t break her promise to Grandma. It never even occurred to me what other promises Mama might break.

Now I came up on the cemetery from the back way, those promises marching through my head. Grandma

had said she’d made Mama promise her two things. One, that she’d stay on her medicine, keep her mood swings under control. Two, that she’d buy Grandma a proper headstone.

Promise number one didn’t make it a full day after Grandma’s funeral. Without Grandma there to count out the pills, Mama decided she didn’t need them. Soon as Daddy pulled out of the driveway for the four-hour drive back to work offshore, Mama flushed her medicine. I found what was left of the capsules floating sideways in the toilet like little lost ships. Mama spent the whole next month propped up in bed with a pillow under her knees, the air conditioner turned up too high. She didn’t say one word when I tiptoed in every evening to kiss her good night.

Mama worked harder at her second promise. After she finally got out of bed, just about all she did for weeks was make drawing after drawing of what she remembered about the Bird Room and drawing after drawing of Grandma’s headstone.

I guess Mama figured a proper tombstone would make up for everything else.

Mama would keep her promise on March 1. Grandma would make her do it.

Now I pushed through the privet, climbed over the lean-to fence, and circled around to the front of the cemetery.

I could still read the sign, just the way I did last summer—HISTORIC PICKENS COUNTY BAPTIST CEMETERY. The sign gave directions to the new home of the Deerfield Baptist Church.

Standing there in the cold, I couldn’t even remember the way it felt that day last summer—to have a mama and a daddy around without even thinking about it.

It was a wonder that time marched on like normal for anybody or anything else. It seemed to me that church sign should have been gone, faded back into the woods, eaten clear through by termites and rot.

Instead, the sign and the graveyard looked…

Smack Dab in the Middle of Maybe

Smack Dab in the Middle of Maybe